4d ago

Podcast #221: The Mountaintop at Grand Geneva Director of Golf & Ski Ryan Brown

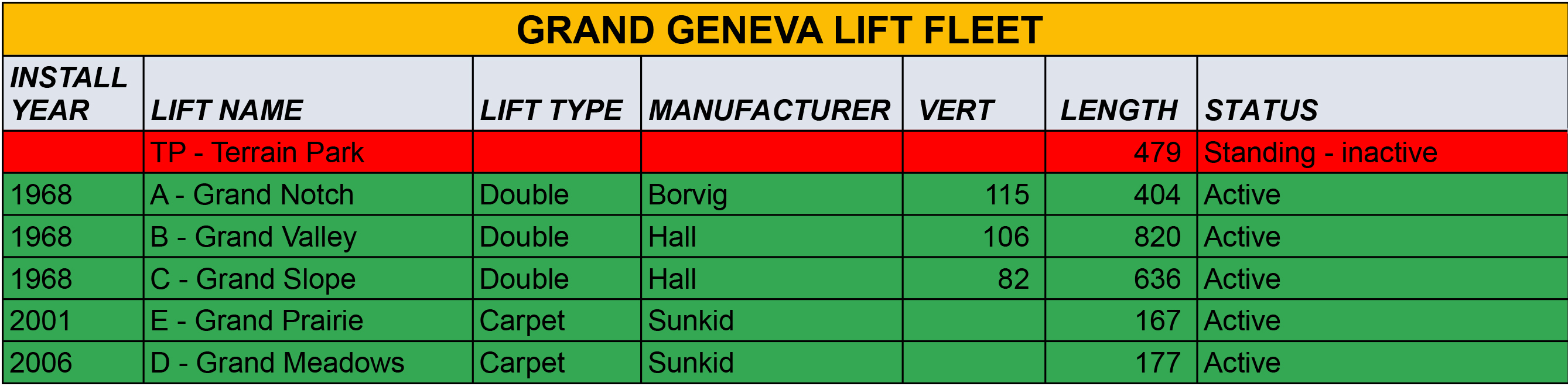

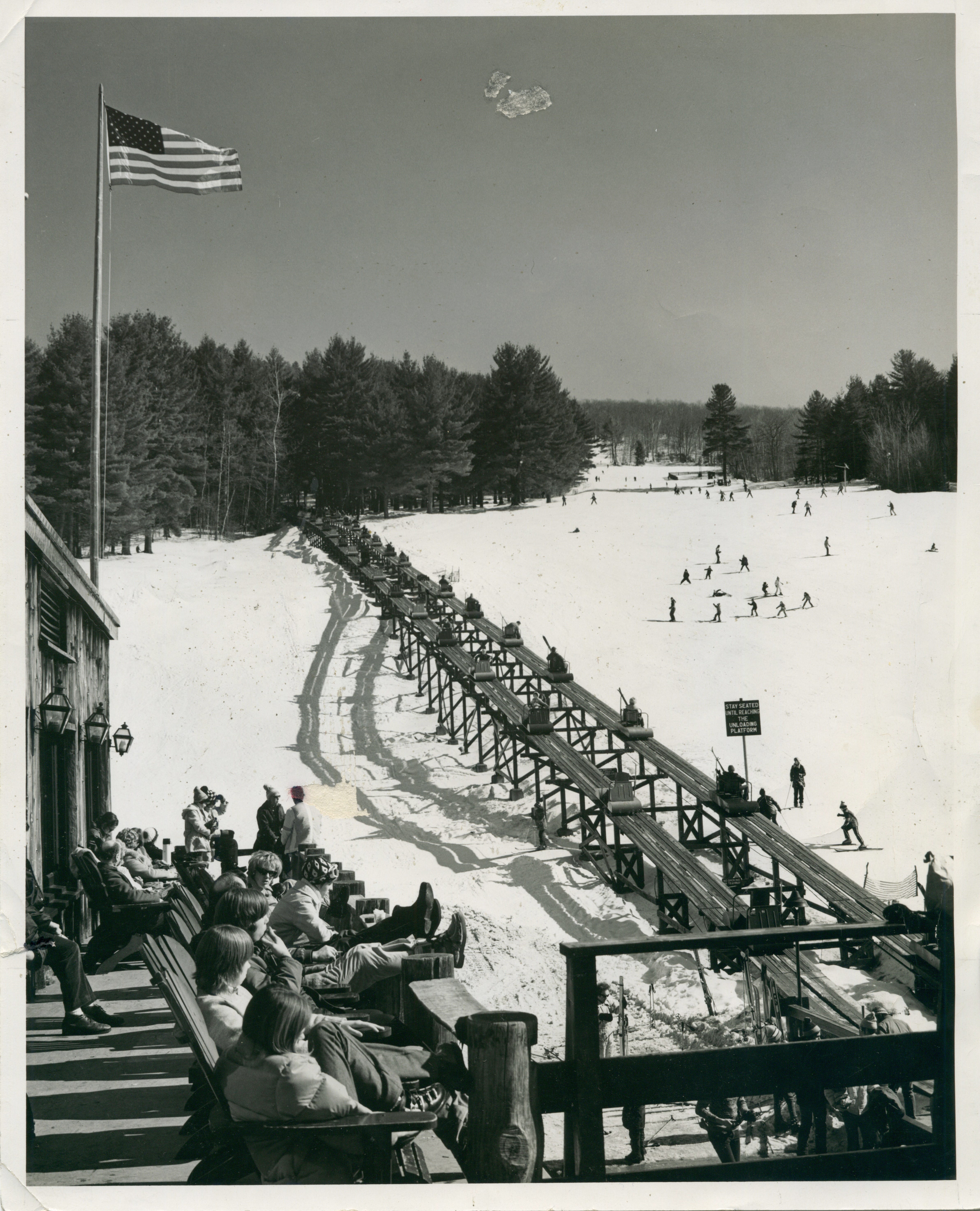

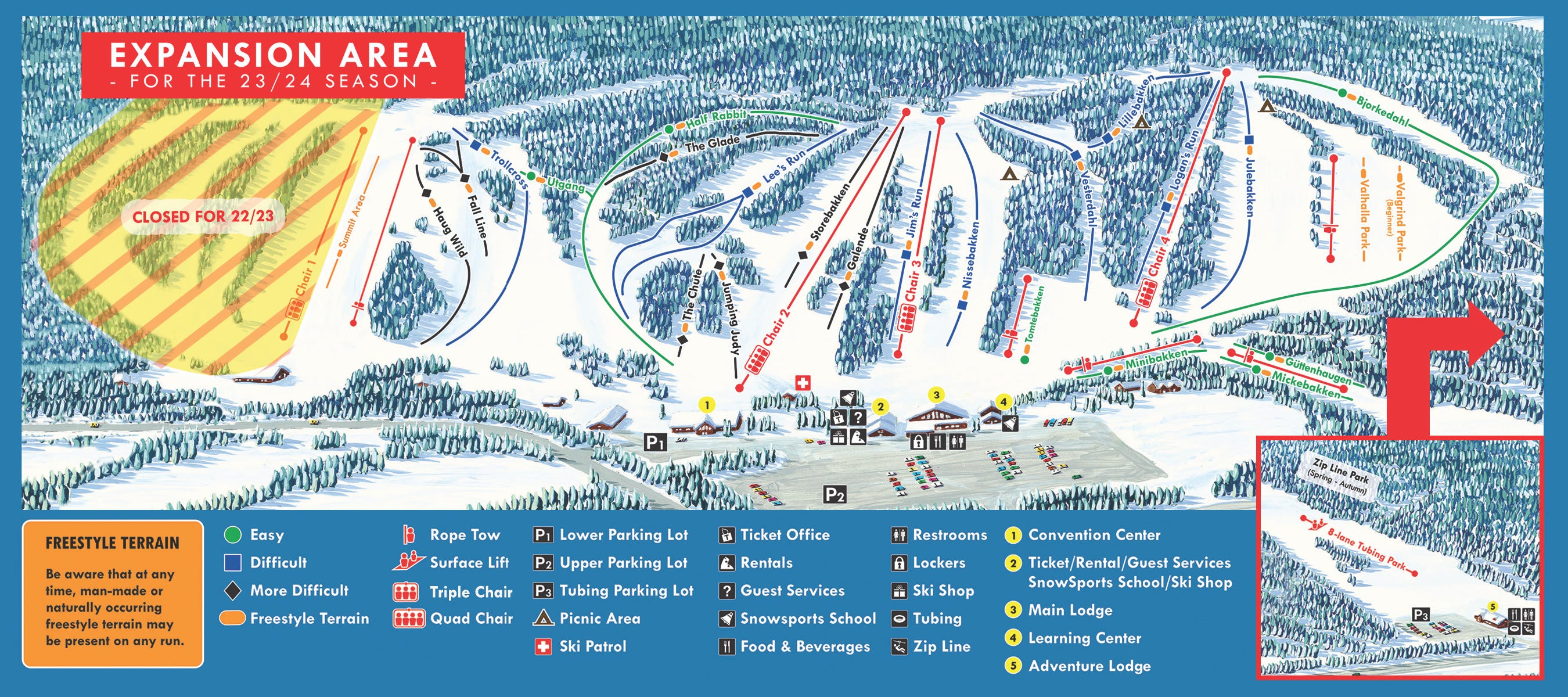

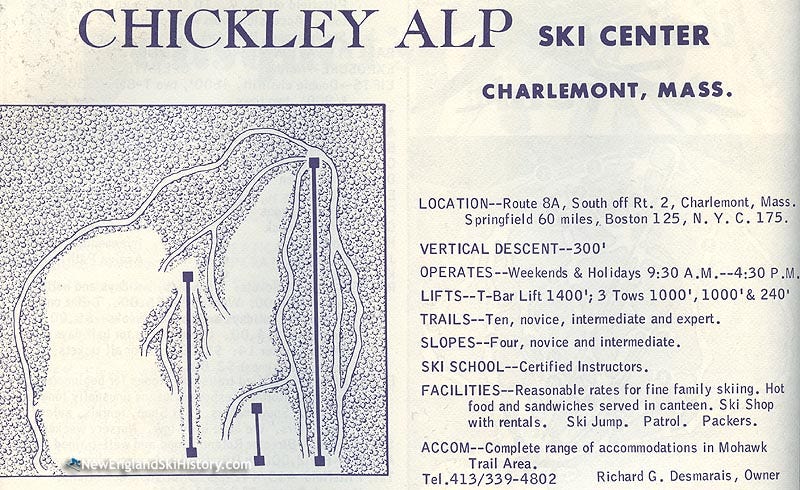

Who Ryan Brown, Director of Golf & Ski at The Mountaintop at Grand Geneva, Wisconsin Recorded on June 17, 2025 About the Mountaintop at Grand Geneva Click here for a mountain stats overview Owned by: Marcus Hotels Located in: Lake Geneva, Wisconsin Year founded: 1968 Pass affiliations: None Closest neighboring U.S. ski areas: Alpine Valley (:23), Wilmot Mountain (:29), Crystal Ridge (:48), Alpine Hills Adventure Park (1:04) Base elevation: 847 feet Summit elevation: 962 feet Vertical drop: 115 feet Skiable acres: 30 Average annual snowfall: 34 inches Trail count: 21 (41% beginner, 41% intermediate, 18% advanced) Lift count: 6 (3 doubles, 1 ropetow, 2 carpets) Why I interviewed him Of America’s various mega-regions, the Midwest is the quietest about its history. It lacks the quaint-town Colonialism and Revolutionary pride of the self-satisfied East, the cowboy wildness and adobe earthiness of the West, the defiant resentment of the Lost Glory South. Our seventh-grade Michigan History class stapled together the state’s timeline mostly as a series of French explorers passing through on their way to somewhere more interesting. They were followed by a wave of industrial loggers who mowed the primeval forests into pancakes. Then the factories showed up. And so the state’s legacy was framed not as one of political or cultural or military primacy, but of brand, the place that stamped out Chevys and Fords by the tens of millions. To understand the Midwest, then, we must look for what’s permanent. The land itself won’t do. It’s mostly soil, mostly flat. Great for farming, bad for vistas. Dirt doesn’t speak to the soul like rock, like mountains. What humans built doesn’t tell us a much better story. Everything in the Midwest feels too new to conceal ghosts. The largest cities rose late, were destroyed in turn by fires and freeways, eventually recharged with arenas and glass-walled buildings that fail to echo or honor the past. Nothing lasts: the Detroit Pistons built the Palace of Auburn Hills in 1988 and developers demolished it 32 years later; the Detroit Lions (and, for a time, the Pistons) played at the Pontiac Silverdome, a titanic, 82,600-spectator stadium that opened in 1976 and came down in 2013 (37 years old). History seemed to bypass the region, corralling the major wars to the east and shooing the natural disasters to the west and south. Even shipwrecks lose their doubloons-and-antique-cannons romance in the Midwest: the Great Lakes most famous downed vessel, the SS Edmund Fitzgerald , sank into Lake Superior in 1975. Her cargo was 26,535 tons of taconite ore pellets. A sad story, but not exactly the sinking of the Titanic . Our Midwest ancestors did leave us one legacy that no one has yet demolished: names. Place names are perhaps the best cultural relics of the various peoples who occupied this land since the glaciers retreated 12,000-ish years ago. Thousands of Midwest cities, towns, and counties carry Native American names. “Michigan” is derived from the Algonquin “Mishigamaw,” meaning “big lake”; “Minnesota” from the Sioux word meaning “cloudy water.” The legacies of French explorers and missionaries live on in “Detroit” (French for “strait”), “Marquette” (17th century French missionary Jacques Marquette), and “Eau Claire” (“clear water”). But one global immigration funnel dominated what became the modern Midwest: 50 percent of Wisconsin’s population descends from German, Nordic, or Scandinavian countries, who arrived in waves from the Colonial era through the early 1900s. The surnames are everywhere: Schmitz and Meyer and Webber and Schultz and Olson and Hanson. But these Old-Worlders came a bit late to name the cities and towns. So they named what they built instead. And they built a lot of ski areas. Ten of Wisconsin’s 34 ski areas carry names evocative of Europe’s cold regions, Scandinavia and the Alps: I wonder what it must have been like, in 18-something-or-other, to leave a place where the Alps stood high on the horizon, where your family had lived in the same stone house for centuries, and sail for God knows how many weeks or months across an ocean, and slow roll overland by oxen cart or whatever they moved about in back then, and at the end of this great journey find yourself in… Wisconsin? They would have likely been unprepared for the landscape aesthetic. Tourism is a modern invention. “The elite of ancient Egypt spent their fortunes building pyramids and having their corpses mummified, but none of them thought of going shopping in Babylon or taking a skiing holiday in Phoenicia [partly in present-day Lebanon, which is home to as many as seven ski areas],” Yuval Noah Harari writes in Sapiens his 2015 “brief history of humankind.” Imagine old Friedrich, who had never left Bavaria, reconstituting his world in the hillocks and flats of the Midwest. Nothing against Wisconsin, but fast-forward 200 years, when the robots can give us a side-by-side of the upper Midwest and the European Alps, and it’s pretty clear why one is a global tourist destination and the other is known mostly as a place that makes a lot of cheese. And well you can imagine why Friedrich might want to summon a little bit of the old country to the texture of his life in the form of a ski area name. That these two worlds - the glorious Alps and humble Wisconsin skiing - overlap, even in a handful of place names, suggests a yearning for a life abandoned, a natural act of pining by a species that was not built to move their life across timezones. This is not a perfect analysis. Most – perhaps none – of these ski areas was founded by actual immigrants, but by their descendants. The Germanic languages spoken by these immigrant waves did not survive assimilation. But these little cultural tokens did. The aura of ancestral place endured when even language fell away. These little ski areas honor that. And by injecting grandiosity into the everyday, they do something else. In coloring some of the world’s most compact ski centers with the aura of some of its most iconic, their founders left us a message: these ski areas, humble as they are, matter. They fuse us to the past and they fuse us to the majesty of the up-high, prove to us that skiing is worth doing anywhere that it can be done, ensure that the ability to move like that and to feel the things that movement makes you feel are not exclusive realms fenced into the clouds, somewhere beyond means and imagination. Which brings us to Grand Geneva, a ski area name that evokes the great Swiss gateway city to the Alps. Too bad reality rarely matches up with the easiest narrative. The resort draws its name from the nearby town of Lake Geneva, which a 19th-century surveyor named not after the Swiss city, but after Geneva, New York, a city (that is apparently named after Geneva, Switzerland), on the shores of Seneca Lake, the largest of the state’s 11 finger lakes. Regardless, the lofty name was the fifth choice for a ski area originally called “Indian Knob.” That lasted three years, until the ski area shuttered and re-opened as the venerable Playboy Ski Area in 1968. More regrettable names followed – Americana Resort from 1982 to ’93, Hotdog Mountain from 1992 to ’94 – before going with the most obvious and least-questionable name, though its official moniker, “The Mountaintop at Grand Geneva” is one of the more awkward names in American skiing. None of which explains the principal question of this sector: why I interviewed Mr. Brown. Well, I skied a bunch of Milwaukee bumps on my drive up to Bohemia from Chicago last year, this was one of them, and I thought it was a cute little place. I also wondered how, with its small-even-for-Wisconsin vertical drop and antique lift collection, the place had endured in a state littered with abandoned ski areas. Consider it another entry into my ongoing investigation into why the ski areas that you would not always expect to make it are often the ones that do. What we talked about Fighting the backyard effect – “our customer base – they don’t really know” that the ski areas are making snow; a Chicago-Milwaukee-Madison bullseye; competing against the Vail-owned mountain to the south and the high-speed-laced ski area to the north; a golf resort with a ski area tacked on; “you don’t need a big hill to have a great park”; brutal Midwest winters and the escape of skiing; I attempt to talk about golf again and we’re probably done with that for a while; Boyne Resorts as a “top golf destination”; why Grand Geneva moved its terrain park; whether the backside park could re-open; “we’ve got some major snowmaking in the works”; potential lift upgrades; no bars on the lifts; the ever-tradeoff between terrain parks and beginner terrain; the ski area’s history as a Playboy Club and how the ski hill survived into the modern era; how the resort moves skiers to the hill with hundreds of rooms and none of them on the trails; thoughts on Indy Pass; and Lake Geneva lake life. What I got wrong We recorded this conversation prior to Sunburst’s joining Indy Pass, so I didn’t mention the resort when discussing Wisconsin ski areas on the product. Podcast Notes On the worst season in the history of the Midwest I just covered this in the article that accompanied the podcast on Treetops, Michigan, but I’ll summarize it this way: the 2023-24 ski season almost broke the Midwest. Fortunately, last winter was better, and this year is off to a banging start. On steep terrain beneath lift A I just thought this was a really unexpected and cool angle for such a little hill. On the Playboy Club From SKI magazine, December 1969 : It is always interesting when giants merge. Last winter Playboy magazine (5.5 million readers) and the Playboy Club (19 swinging nightclubs from Hawaii to New York to Jamaica, with 100,000 card-carrying members) in effect joined the sport of skiing, which is also a large, but less formal, structure of 3.5 million lift-ticket-carrying members. The resulting conglomerate was the Lake Geneva Playboy Club-Hotel, Playboy’s ski resort on the rolling plains of Wisconsin. The Playboy Club people must have borrowed the idea of their costumed Bunny Waitress from the snow bunny of skiing fame, and since Playboy and skiing both manifestly devote themselves to the pleasures of the body, some sort of merger was inevitable. Out of this union, obviously, issued the Ultimate Ski Bunny – one able to ski as well as sport the scanty Bunny costume to lustrous perfection. That’s a bit different from how the resort positions its ski facilities today: Enjoy southern Wisconsin’s gem - our skiing and snow resort in the countryside of Lake Geneva, with the best ski hills in Wisconsin. The Mountain Top at Grand Geneva Resort & Spa boasts 20 downhill ski runs and terrain designed for all ages, groups and abilities, making us one of the best ski resorts in Wisconsin. Just an hour from Milwaukee and Chicago, our ski resort in Lake Geneva is close enough to home for convenience, but far enough for you and your family to have an adventure. Our ultimate skier’s getaway offers snowmaking abilities that allow our ski resort to stay open even when there is no snow falling. The Mountain Top offers ski and snow accommodations, such as trolley transportation available from guest rooms at Grand Geneva and Timber Ridge Lodge , three chairlifts, two carpet lifts, a six-acre terrain park, excellent group rates, food and drinks at Leinenkugel’s Mountain Top Lodge and even night skiing. We have more than just skiing! Enjoy Lake Geneva sledding, snowshoeing and cross-country skiing too. Truly something for everyone at The Mountain Top ski resort in Lake Geneva. No ski equipment? No problem with the Learn to Ride rentals . Come experience The Mountain Top at Grand Geneva and enjoy the best skiing around Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. On lost Wisconsin and Midwest ski areas The Midwest Lost Ski Areas Project counts 129 lost ski areas in Wisconsin. I’ve yet to order these Big Dumb Chart-style , but there are lots of cool links in here that can easily devour your day. The Storm explores the world of North American lift-served skiing year-round. Join us. Get full access to The Storm Skiing Journal and Podcast at www.stormskiing.com/subscribe

Dec 16

Podcast #220: Stowe Mountain VP & GM Mike Giorgio

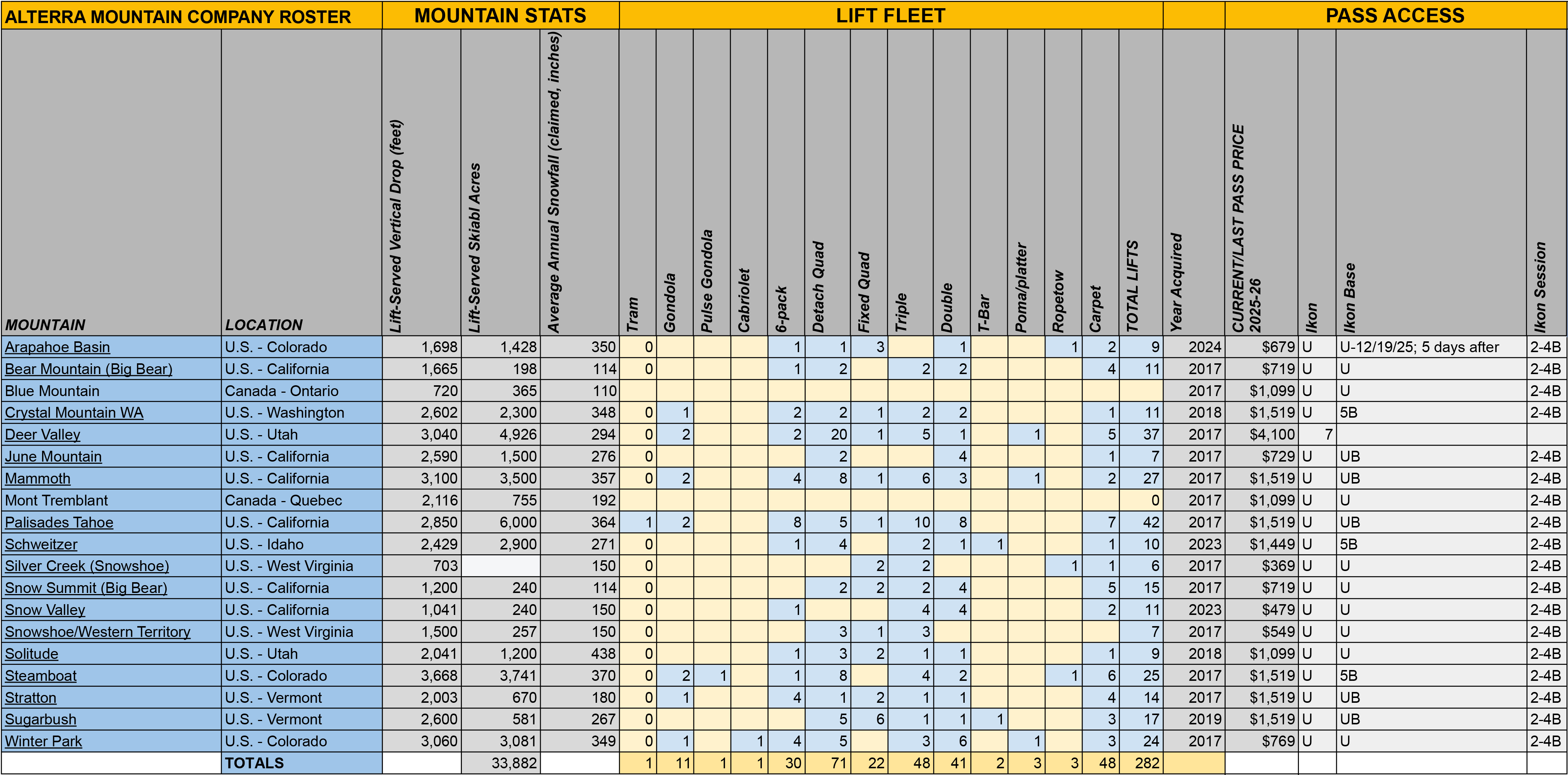

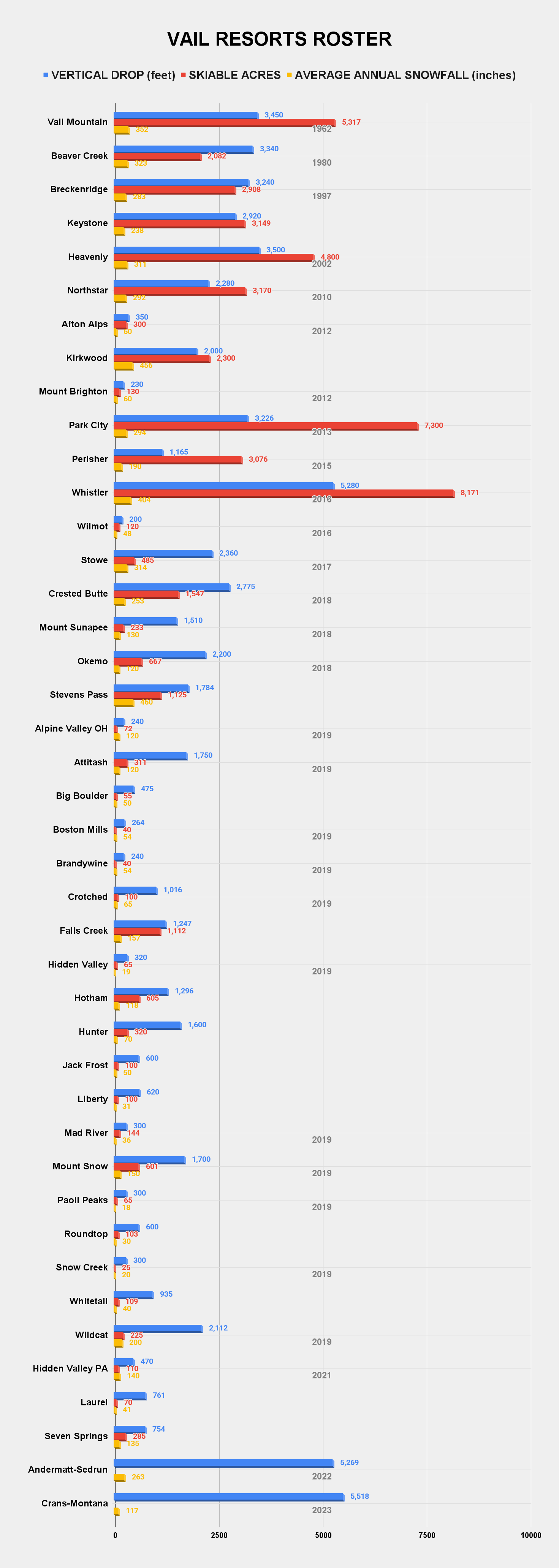

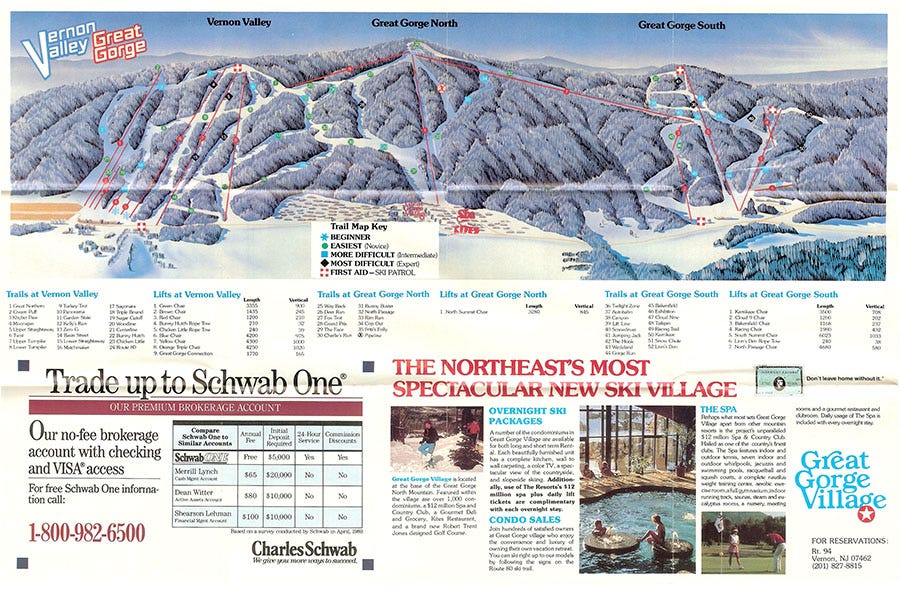

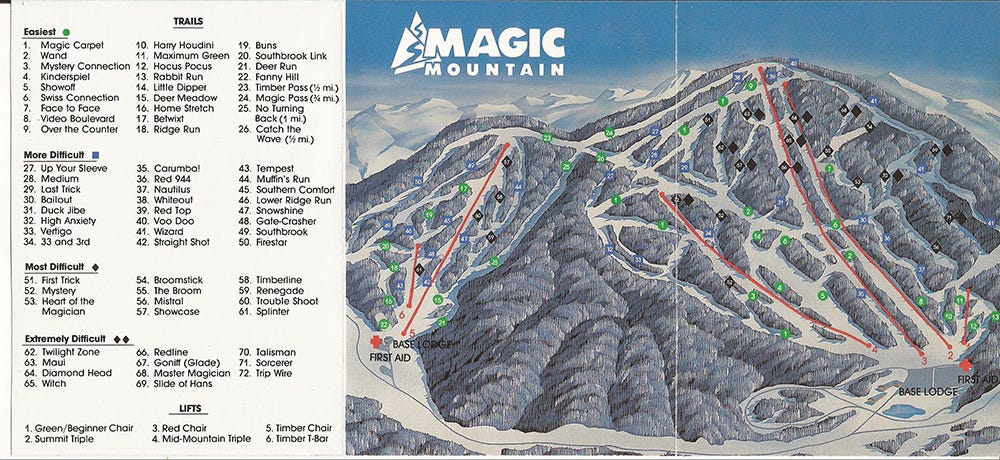

Who Mike Giorgio, Vice President and General Manager of Stowe Mountain , Vermont Recorded on October 8, 2025 About Stowe Click here for a mountain stats overview Owned by: Vail Resorts, which also owns: Located in: Stowe, Vermont Year founded: 1934 Pass affiliations: * Epic Pass: unlimited access * Epic Local Pass: unlimited access with holiday blackouts * Epic Northeast Value Pass: 10 days with holiday blackouts * Epic Northeast Midweek Pass: 5 midweek days with holiday blackouts * Access on Epic Day Pass All and 32 Resort tiers * Ski Vermont 4 Pass – up to one day, with blackouts * Ski Vermont Fifth Grade Passport – 3 days, with blackouts Closest neighboring U.S. ski areas: Smugglers’ Notch (ski-to or 40-ish-minute drive in winter, when route 108 is closed over the notch), Bolton Valley (:45), Cochran’s (:50), Mad River Glen (:55), Sugarbush (:56) Base elevation: 1,265 feet (at Toll House double) Summit elevation: 3,625 feet (top of the gondola), 4,395 feet at top of Mt. Mansfield Vertical drop: 2,360 feet lift-served, 3,130 feet hike-to Skiable acres: 485 Average annual snowfall: 314 inches Trail count: 116 (16% beginner, 55% intermediate, 29% advanced) Lift count: 12 (1 eight-passenger gondola, 1 six-passenger gondola, 1 six-pack, 3 high-speed quads, 1 fixed-grip quad, 1 triple, 2 doubles, 2 carpets) Why I interviewed him There is no Aspen of the East, but if I had to choose an Aspen of the East, it would be Stowe. And not just because Aspen Mountain and Stowe offer a similar fierce-down, with top-to-bottom fall-line zippers and bumpy-bumps spliced by massive glade pockets. Not just because each ski area rises near the far end of densely bunched resorts that the skier must drive past to reach them. Not just because the towns are similarly insular and expensive and tucked away. Not just because the wintertime highway ends at both places, an anachronistic act of surrender to nature from a mechanized world accustomed to fencing out the seasons. And not just because each is a cultural stand-in for mechanized skiing in a brand-obsessed, half-snowy nation that hates snow and is mostly filled with non-skiers who know nothing about the activity other than the fact that it exists. Everyone knows about Aspen and Stowe even if they’ll never ski, in the same way that everyone knows about LeBron James even if they’ve never watched basketball. All of that would be sufficient to make the Stowe-is-Aspen-East argument. But the core identity parallel is one that threads all these tensions while defying their assumed outcome. Consider the remoteness of 1934 Stowe and 1947 Aspen, two mountains in the pre-snowmaking, pre-interstate era, where cutting a ski area only made sense because that’s where it snowed the most. Both grew in similar fashion. First slowly toward the summit with surface lifts and mile-long single chairs crawling up the incline. Then double chairs and gondolas and snowguns and detachable chairlifts. A ski area for the town evolves into a ski area for the world. Hotels a la luxe at the base, traffic backed up to the interstate, corporate owners and $261 lift tickets. That sounds like a formula for a ruined world. But Stowe the ski area, like Aspen Mountain the ski area, has never lost its wild soul. Even buffed out and six-pack equipped and Epic Pass-enabled, Stowe remains a hell of a mountain, one of the best in New England, one of my favorite anywhere. With its monster snowfalls, its endless and perfectly spaced glades, its never-groomed expert zones, its sprawling footprint tucked beneath the Mansfield summit, its direct access to rugged and forbidding backcountry, Stowe, perhaps the most western-like mountain in the East, remains a skier’s mountain, a fierce and humbling proving ground, an any-skier’s destination not because of its trimmings, but because of the Christmas tree itself. Still, Stowe will never be Aspen, because Stowe does not sit at 8,000 feet and Stowe does not have three accessory ski areas and Stowe the Town does not grid from the lift base like Aspen the Town but rather lies eight miles down the road. Also Stowe is owned by Vail Resorts, and can you just imagine? But in a cultural moment that assumes ski area ruination-by-the-consolidation-modernization-mega-passification axis-of-mainstreaming, Aspen and Stowe tell mirrored versions of a more nuanced story. Two ski areas, skinned in the digital-mechanical infrastructure that modernity demands, able to at once accommodate the modern skier and the ancient mountain, with all of its quirks and character. All of its amazing skiing. What we talked about Stowe the Legend; Vail Resorts’ leadership carousel; ascending to ski area leadership without on-mountain experience; Mount Brighton, Michigan and Midwest skiing; struggles at Paoli Peaks, Indiana; how the Sunrise six-pack upgrade of the old Mountain triple changed the mountain; whether the Four Runner quad could ever become a six-pack; considering the future of the Lookout Double and Mansfield Gondola; who owns the land in and around the ski area; whether Stowe has terrain expansion potential; the proposed Smugglers’ Notch gondola connection and whether Vail would ever buy Smuggs; “you just don’t understand how much is here until you’re here”; why Stowe only claims 485 acres of skiable terrain; protecting the Front Four; extending Stowe’s season last spring; snowmaking in a snowbelt; the impact and future of paid parking; on-mountain bed-base potential; Epic Friend 50 percent off lift tickets; and Stowe locals and the Epic Pass. What I got wrong On details I noted that one of my favorite runs was not a marked run at all: the terrain beneath the Lookout double chair. In fact, most of the trail beneath this mile-plus-long lift is a market run called, uh, “Lookout.” So I stand corrected. However, the trailmap makes this full-throttle, narrow bumper – which feels like skiing on a rising tide – look wide, peaceful, and groomable. It is none of those things, at least for its first third or so. On skiable acres * I said that Killington claimed “like 1,600 acres” of terrain – the exact claimed number is 1,509 acres. * I said that Mad River Glen claimed far fewer skiable acres than it probably could, but I was thinking of an out-of-date stat. The mountain claims just 115 acres of trails – basically nothing for a 2,000-vertical-foot mountain, but also “800 acres of tree-skiing access.” The number listed on the Pass Smasher Deluxe is 915 acres. On season closings I intimated that Stowe had always closed the third weekend in April. That appears to be mostly true for the past two-ish decades, which is as far back as New England Ski History has records. The mountain did push late once, however, in 2007, and closed early during the horrible no-snow winter of 2011-12 (April 1), and the Covid-is-here-to-kill-us-all shutdown of 2020 (March 14). On doing better prep I asked whether Stowe had considered making its commuter bus free, but it, um, already is. That’s called Reeserch, Folks. On lift ticket rates I claimed that Stowe’s top lift ticket price would drop from $239 last year to $235 this coming season, but that’s inaccurate. Upon further review, the peak walk-up rate appears to be increasing to $261 this coming winter: Which means Vail’s record of cranking Stowe lift ticket rates up remains consistent: On opening hours I said that the lifts at Stowe sometimes opened at “7:00 or 7:30,” but the earliest ski lift currently opens at 8:00 most mornings (the Over Easy transit gondola opens at 7:30). The Fourrunner quad used to open at 7:30 a.m. on weekends and holidays. I’m not sure when mountain ops changed that. Here’s the lift schedule clipped from the circa 2018 trailmap: On Mount Brighton, Michigan’s supposed trashheap legacy I’d read somewhere, sometime, that Mount Brighton had been built on dirt moved to make way for Interstate 96, which bores across the state about a half mile north of the ski area. The timelines match, as this section of I-96 was built between 1956 and ’57, just before Brighton opened in 1960. This circa 1962 article from The Livingston Post , a local paper, fails to mention the source of the dirt, leaving me uncertain as to whether or not the hill is related to the highway: Why you should ski Stowe From my April 10 visit last winter, just cruising mellow, low-angle glades nearly to the base: I mean, the place is just: I love it, Man. My top five New England mountains, in no particular order, are Sugarbush, Stowe, Jay, Smuggs, and Sugarloaf. What’s best on any given day depends on conditions and crowding, but if you only plan to ski the East once, that’s your list. Podcast Notes On Stowe being the last 1,000-plus-vertical-foot Vermont ski area that I featured on the pod You can view the full podcast catalogue here . But here are the past Vermont eps: * Killington & Pico – 2019 | 2023 | 2025 * Stratton 2024 * Okemo 2023 * Middlebury Snowbowl 2023 * Mount Snow 2020 | 2023 * Bromley 2022 * Jay Peak 2022 | 2020 * Smugglers’ Notch 2021 * Bolton Valley 2021 * Hermitage Club 2020 * Sugarbush 2020 with current president John Hammond | 2020 with past owner Win Smith * Mad River Glen 2020 * Magic Mountain 2019 | 2020 * Burke 2019 On Stowe having “peers, but no betters” in New England While Stowe doesn’t stand out in any one particular statistical category, the whole of the place stacks up really well to the rest of New England - here’s a breakdown of the 63 public ski areas that spin chairlifts across the six-state region: On the Front Four ski runs The “Front Four” are as synonymous with Stowe as the Back Bowls are with Vail Mountain or Corbet’s Couloir is with Jackson Hole. These Stowe trails are steep, narrow, double-plus-fall-line bangers that, along with Castlerock at Sugarbush and Paradise at Mad River Glen, are among the most challenging runs in New England. The problem is determining which of the double-blacks spiderwebbing off the top of Fourrunner are part of the Front Four. Officially, the designation has always bucketed National, Liftline, Goat, and Starr together, but Bypass, Haychute, and Lookout could sub in most days. Credit to Stowe for keeping these wild trails intact for going on a century, but what I said about them “not being for the masses” on the podcast wasn’t quite accurate, as the lower portions of many - especially Liftline - are wide, often groomed, and not particularly treacherous. The best end-to-end trail is Goat, which is insanely steep and narrow up top. Here’s part of Goat’s middle-to-lower section, which is mellower but a good portrayal of New England bumpy, exposed-dirt-and-rocks gnar, especially at the :19 mark: The most glorious ego boost (or ego check) is the few hundred vertical feet of Liftline directly below Fourrunner. Sound on for scrapey-scrape: When the cut trails get icy, you can duck into the adjacent glades, most of which are unmarked but skiable. Here, I bailed into the trees skier’s left of Starr to escape the ice rink: On Vail Resorts’ leadership shuffles Twelve of Vail’s 37 North American ski areas began the 2024-25 ski season with a different leader than they ended the 2023-24 ski season with. This included five of the company’s New England resorts, including Stowe. Giorgio, in fact, became the ski area’s third general manager in three winters, and the fourth since Vail acquired the ski area in 2017. I asked Giorgio about this, as a follow up to a similar set of questions I’d laid out for Vail Resorts CEO Rob Katz in August: I may be overthinking this, but check this out: between 2017 and 2024, Vail Resorts changed leadership at its North American ski areas more than 70 times - the yellow boxes below mark a new president-general-manager equivalent (red boxes indicate that Vail did not yet own the ski area): To reset my thinking here: I can’t say that this constant leadership shuffle is inherently dysfunctional, and most Vail Resorts employees I speak with appreciate the company’s upward-mobility culture. And I consistently find Vail’s mountain leaders - dozens of whom I have hosted on this podcast - to be smart, earnest, and caring. However, it’s hard to imagine that the constant turnover in top management isn’t at least somewhat related to Vail Resorts’ on-the-ground reputational issues, truncated seasons at non-core ski areas (see Paoli Peaks section below), and general sense that the company’s arc of investment bends toward its destination resorts. On Peak Resorts Vail purchased all of Peak Resorts, including Mount Snow, where Giorgio worked, in 2019. Here’s that company’s growth timeline: On Vernon Valley-Great Gorge The ski area now known as Mountain Creek was Vernon Valley-Great Gorge until 1997. Anyone who grew up in the area still calls the joint by its legacy name. On Paoli Peaks versus Perfect North My hope is that if I complain enough about Paoli Peaks, Vail will either invest enough in snowmaking to tranform it into a functional ski area or sell it. Here are the differences between Paoli’s season lengths since 2013 as compared to Perfect North, its competitor that is the only other active ski area in the state: What explains this longstanding disparity, which certainly predates Vail’s 2019 acquisition of the ski area? Paoli does sit southwest of Perfect North, but its base is 200 feet higher (600 feet, versus 400 for Perfect), so elevation doesn’t explain it. Perfect does benefit from a valley location, which, longtime GM Jonathan Davis told me a few years back, locks in the cold air and supercharges snowmaking. The simplest answer, however, is probably the correct one: Perfect North has built one of the most impressive snowmaking systems on the planet, and they use it aggressively, cranking more than 200 guns at once. At peak operations, Perfect can transform from green grass to skiable terrain in just a couple of days. So yes, Perfect has always been a better operation than Paoli. But check this out: Paoli’s performance as compared to Perfect’s has been considerably worse in the five full seasons of Vail Resorts’ ownership (excluding 2019-20), than in the six seasons before, with Perfect besting Paoli to open by an average of 21 days before Vail arrived, and by 31 days after. Perfect’s seasons lasted an average of 25 days longer than Paoli’s before Vail arrived, and 38 days longer after: Yes, Paoli is a uniquely challenged ski area, but I’m confident that someone can do a better job running this place than Vail has been doing since 2019. Certainly, that someone could be Vail, which has the resources and institutional knowledge to transform this, or any ski area, into a center of SnoSportSkiing excellence. So far, however, they have declined to do so, and I keep thinking of what Davis, Perfect North’s longtime GM, said on the pod in 2022: “If Vail doesn’t want [its ski areas in Indiana and Ohio], we’ll take them!” On the 2022 Sunrise Six replacement for the triple In 2022, Stowe replaced the Mountain triple chair, which sat up a flight of steep steps from the parking lot, with the at-grade Sunrise six-pack. It was the kind of big-time lift upgrade that transforms the experience of an entire ski area for everyone, whether they use the new lift or not, by pulling skiers toward a huge pod of underutilized terrain and away from longtime alpha lifts Fourrunner and the Mansfield Gondola. On Fourrunner as a vert machine Stowe’s Fourruner high-speed quad is one of the most incredible lifts in American skiing, a lightspeed-fast base-to-summit, 2,040-vertical-foot monster with direct access to some of the best terrain east of A-Basin. The highest vert total in my 54-day 2024-25 ski season came (largely) courtesy of this lift - and I only skied five-and-a-half hours: On Stowe-Smuggs proximity and the proposed gondola and a long drive in winter Adventurous skiers can skin or hike across the top of Stowe’s Spruce Peak and ski down into the Smugglers’ Notch ski area. An official ski trail once connected them, and Smuggs proposed a gondola connector a couple of years back. If Vail were to purchase sprawling Smuggs, a Canyons-Park City mega-connection – while improbable given local environmental lobbies -could instantly transform Stowe into one of the largest ski areas in the East. On Jay Peak’s big snowmaking upgrades I referenced big offseason snowmaking upgrades for water-challenged (but natural-snow blessed), Jay Peak. I was referring to this : This season brings an over $1.5M snowmaking upgrade that’s less about muscle and more about brains. We’ve added 49 brand new HKD Low E air-water snowmaking guns—32 on Queen’s Highway and 17 on Perry Merrill. These aren’t your drag-’em-out, hook-’em-up, hope-it’s-cold-enough kind of guns. They’re fixed in place for the season and far more efficient, using much less compressed air than the ones they replace. Translation: better snow, less energy. On Perry Merrill, things get even slicker. We’ve installed HKD Klik automated hydrants that come with built-in weather stations. The second temps hit 28 degrees wetbulb, these hydrants kick on automatically and adjust the flow as the mercury drops. No waiting, no guesswork, no scrambling the crew. The end result? Those key connecting trails between Tramside and Stateside get covered faster, which means you can ski from one side to the other—or straight back to your condo—without having to hop on a shuttle with your boots still buckled. … It’s all part of a bigger 10-year snowmaking plan we’re rolling out—more automation, better efficiency, and ultimately, better snow for you to ski and ride on. The Storm explores the world of lift-served skiing year-round. Join us. Get full access to The Storm Skiing Journal and Podcast at www.stormskiing.com/subscribe

Dec 5

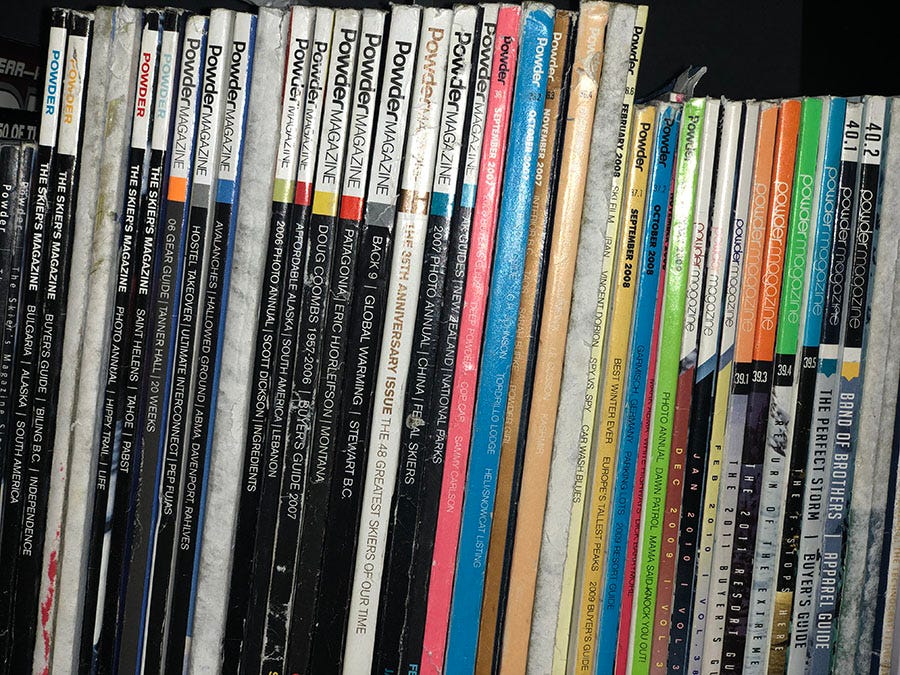

Podcast #219: Mount Bohemia Owner Lonie Glieberman

The Storm explores the world of lift-served skiing year-round. Join us. Who Lonie Glieberman, Founder, Owner, & President of Mount Bohemia , Michigan Recorded on November 19, 2025 About Mount Bohemia Click here for a mountain stats overview Owned by: Lonie Glieberman Located in: Lac La Belle, Michigan Year founded: 2000, by Lonie Pass affiliations: None Reciprocal partners: Boho has developed one of the strongest reciprocal pass programs in the nation, with lift tickets to 34 partner mountains. To protect the mountain’s more distant partners from local ticket-hackers, those ski areas typically exclude in-state and border-state residents from the freebies. Here’s the map: And here’s the Big Dumb Storm Chart detailing each mountain and its Boho access: Closest neighboring ski areas: Mont Ripley (:50) Base elevation: 624 feet Summit elevation: 1,522 feet Vertical drop: 898 feet Skiable acres: 585 Average annual snowfall: 273 inches Trail count: It’s hard to say exactly, as Boho adds new trails every year, and its map is one of the more confusing ones in American skiing, both as you try analyzing it on this screen, and as you’re actually navigating the mountain. My advice is to not try too hard to make the trailmap make sense. Everything is skiable with enough snow, and no matter what, you’re going to end up back at one of the two chairlifts or the road, where a shuttlebus will come along within a few minutes. Lift count: 2 (1 triple, 1 double) Why I interviewed him For those of us who lived through a certain version of America, Mount Bohemia is a fever dream, an impossible thing, a bantered-about-with-friends-in-a-basement-rec-room-idea that could never possibly be. This is because we grew up in a world in which such niche-cool things never happened. Before the internet spilled from the academic-military fringe into the mainstream around 1996, We The Commoners fed our brains with a subsistence diet of information meted out by institutional media gatekeepers. What I mean by “gatekeepers” is the limited number of enterprises who could afford the broadcast licenses, printing presses, editorial staffs, and building and technology infrastructure that for decades tethered news and information to costly distribution mechanisms. In some ways this was a better and more reliable world: vetted, edited, fact-checked. Even ostensibly niche media – the Electronic Gaming Monthly and Nintendo Power magazines that I devoured monthly – emerged from this cubicle-in-an-office-tower Process that guaranteed a sober, reality-based information exchange. But this professionalized, high-cost-of-entry, let’s-get-Bob’s-sign-off-before-we-run-this, don’t-piss-off-the-advertisers world limited options, which in turn limited imaginations – or at least limited the real-world risks anyone with money was willing to take to create something different. We had four national television networks and a couple dozen cable channels and one or two local newspapers and three or four national magazines devoted to niche pursuits like skiing. We had bookstores and libraries and the strange, ephemeral world of radio. We had titanic, impossible-to-imagine-now big-box chain stores ordering the world’s music and movies into labelled bins, from which shoppers could hope – by properly interpreting content from box-design flare or maybe just by luck – to pluck some soul-altering novelty. There was little novelty. Or at least, not much that didn’t feel like a slightly different version of something you’d already consumed. Everything, no matter how subversive its skin, had to appeal to the masses, whose money was required to support the enterprise of content creation. Pseudo-rebel networks such as ESPN and MTV quickly built global brands by applying the established institutional framework of network television to the mainstream-but-information-poor cultural centerpieces of sports and music. This cultural sameness expressed itself not just in media, but in every part of life: America’s brand-name sprawl-ture (sprawl culture) of restaurants and clothing stores and home décor emporia; its stuff-freeways-through-downtown ruining of our great cities; its three car companies stamping out nondescript sedans by the millions. Skiing has long acted as a rebel’s escape from staid American culture, but it has also been hemmed in by it. Yes, said Skiing Incorporated circa 1992, we can allow a photo of some fellow jumping off a cliff if it helps convince Nabisco Bob fly his family out to Colorado for New Year’s, so long as his family is at no risk of actually locating any cliffs to jump off of upon arrival. After all, 1992 Bob has no meaningful outlet through which to highlight this advertising-experience disconnect. The internet broke this whole system. Everywhere, for everything. If I wanted, say, a Detroit Pistons hoodie in 1995, I had to drive to a dozen stores and choose the least-bad version from the three places that stocked them. Today I have far more choice at far less hassle: I can browse hundreds of designs online without leaving the house. Same for office furniture or shoes or litterboxes or laundry baskets or cars. And especially for media and information. Consumer choice is greater not only because the internet eliminated distance, but also because it largely eliminated the enormous costs required to actualize a tangible thing from the imagination. There were trade-offs, of course. Our current version of reality has too many options, too many poorly made products, too much bad information. But the internet did a really good job of democratizing preferences and uniting dispersed communities around niche interests. Yes, this means that a global community of morons can assemble over their shared belief that the planet is flat, but it also means that legions of Star Wars or Marvel Comics or football obsessives can unite to demand more of these specific things. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the dormant Star Wars and Marvel franchises rebooted in spectacular, omnipresent fashion within a decade of the .com era’s dawn. The trajectory was slightly different in skiing. The big-name ski areas today are largely the same set of big-name ski areas that we had 30 years ago, at least in America (Canada is a very different story). But what the internet helped bring to skiing was an awareness that the desire for turns outside of groomed runs was not the hyper-specific desire of the most dedicated, living-in-a-campervan-with-their-dog skiers, but a relatively mainstream preference. Established ski areas adapted, adding glades and terrain parks and ungroomed zones. The major ski areas of 2025 are far more interesting versions of the ski areas that existed under the same names in 1995. Dramatic and welcome as these additions were, they were just additions. No ski area completely reversed itself and shut out the mainstream skier. No one stopped grooming or eliminated their ski school or stopped renting gear. But they did act as something of a proof-of-concept for minimalist ski areas that would come online later, including avy-gear-required, no-grooming Silverton, Colorado in 2001, and, at the tip-top of the American Midwest, in a place too remote for anyone other than industrial mining interests to bother with, the ungroomed, snowmaking-free Mount Bohemia. I can’t draw a direct line between the advent of the commercial internet and the rise of Mount Bohemia as a successful niche business within a niche industry. But I find it hard to imagine one without the other. The pre-internet world, the one that gave us shopping malls and laugh-track sitcoms and standard manual transmissions, lacked the institutional imagination to actualize skiing’s most dynamic elements in the form of a wild and remote pilgrimage site. Once the internet ordered fringe freeskiing sentiments into a mainstream coalition, the notion of an extreme ski area seemed inevitable. And Bohemia, without a basically free global megaphone to spread word of its improbable existence, would struggle to establish itself in a ski industry that dismissed the concept as idiotic and with a national ski media that considered the Midwest irrelevant. Even with the internet, Boho took a while to catch on, as Lonie detailed in his first podcast appearance three years ago. It probably took the mainstreaming of social media, starting around 2008, to really amp up the online echo-sphere and help skiers understand this gladed, lake-effect-bombed kingdom at the end of the world. Whatever drove Boho’s success, that success happened. This is a good, stable business that proved that ski areas do not have to cater to all skiers to be viable. But those of us who wanted Bohemia before it existed still have a hard time believing that it does. Like superhero movies or video-calls or energy drinks that aren’t coffee, Boho is a thing we could, in the ‘80s and early ‘90s, easily imagine but just as easily dismiss as fantasy. Fortunately, our modern age of invention and experimentation includes plenty of people who dismiss the dismissers, who see things that don’t exist yet and bring them into our world. And one of the best contributions to skiing to emerge from this age is Mount Bohemia. What we talked about Season pass price and access changes; lifetime and two-year season passes; a Disney-ski comparison that isn’t negative; when your day ticket costs as much as your season pass; Lonie’s dog makes a cameo; not selling lift tickets on Saturdays; “too many companies are busy building a brand that no one will hate, versus a brand that someone will love”; why it’s OK to have some people be angry with you; UP skiing’s existential challenge; skiing’s vibe shift from competition to complementary culture; the Midwest’s advanced-skier problem; Boho’s season pass reciprocal program; why ski areas survive; the Keweenaw snow stake and Boho’s snowfall history; recent triple chair improvements and why Boho didn’t fully replace the chair – “it’s basically a brand-new chairlift”; a novel idea for Boho’s next new chairlift; the Nordic spa; proposed rezoning drama; housing at the end of the world; could Mount Bohemia have a Mad River Glen co-op-style future?; why the pass deadline really is the pass deadline; and Mount Bohemia TV. What I got wrong * I said that Boho’s one-day lift ticket was “$89 or $92” last time Lonie joined me on the pod, in fall, 2022. The one-day cost for the 2022-23 ski season was $87. * I said that Powder Mountain, Utah, may extend their no-lift-ticket-sales-on-Saturdays-and-Sundays-in-February policy, which the mountain rolled out last year, to other dates, but their sales calendar shows just eight restricted dates (one of which is Sunday, March 1), which is the same number as last winter. Why you should ski Mount Bohemia I can’t add anything useful to this bit that I wrote a few months back: Or didn’t say three years ago, around my first Boho pod: Podcast Notes On Boho’s season pass On Lonie’s Library A Boho podcast will always come loaded with some Lonie Library recommendations. In this episode, we get The Power of Cult Branding by Mattew W. Ragas and Bolivar J. Bueno and The 22 Immutable Laws of Branding by Al Ries and Laura Ries. On Raising Cane’s Lonie tells us about a restaurant called Raising Cane’s that sells nothing but chicken fingers. Because I have this weird way of sometimes not noticing super-obvious things, I’d never heard of the place. But apparently they have 900-ish locations , including several here in NYC. I’m sure you already know this. On Jimmy Buffett Then again I’m sometimes overly attuned to things that I think everyone knows about, like Jimmy Buffett. Probably most people are aware of his Margaritaville -headlined music catalog, but perhaps not the Boomers-Gone-Wild Parrothead energy of his concerts, which were mass demonstrations of a uniquely American weirdness that’s impossible to believe in unless you see it: I don’t know if I’d classify this spectacle as sports for people who don’t like sports or anthropological proof that mass coordinated niche crowd-dancing predates the advent of TikTok, but I hope this video reaches the aliens first and they decide not to bother. On “when we spoke in Milwaukee” This was the second time I’ve interviewed Lonie recently. The first was in front of an audience at the Snowvana ski show in Milwaukee last month. We did record that session, and it was different enough from this pod to justify releasing – I just don’t have a timeline on when I’ll do that yet. Here’s the preview article that outlined the event: On Lonie operating the Porcupine Mountains ski area I guess you can make anything look rad. Porcupine Mountains ski area, as presented today under management of the State of Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources: The same ski area under Lonie’s management, circa 2011: On the owner of Song and Labrador, New York buying and closing nearby Toggenburg ski area On Indy’s fight with Ski Cooper I wrote two stories on this, each of which subtracted five years from my life. The first: The follow-up: On Snow Snake, Apple Mountain, and Mott Mountain ski areas These three Mid-Michigan ski areas were so similar it was frightening – the only thing I can conclude from the fact that Snow Snake is the only one left is that management trumps pretty much everything when it comes to which ski areas survive: On Crystal Mountain, Michigan versus Sugar Loaf, Michigan I noted that 1995 Stu viewed Sugar Loaf as a “more interesting” ski area than contemporary Crystal. It’s important to note that this was pre-expansion Crystal, before the ski area doubled in size with backside terrain. Here are the Crystal versus Sugar Loaf trailmaps of that era: I discussed all of this with Crystal CEO John Melcher last year: On Thunder Mountain and Walloon Hills Lonie mentions two additional lost Michigan ski areas: Thunder Mountain and Walloon Hills. The latter, while stripped of its chairlifts, still operates as a nonprofit called Challenge Mountain. Here’s what it looked like just before shuttering as a public ski area in 1978: The responsible party here was nearby Boyne, which bought both Walloon and Thunder in 1967. They closed the latter in 1984: The company now known as Boyne Resorts purchased a total of four Michigan ski areas after Everett Kircher founded Boyne Mountain in 1948, starting with The Highlands in 1963. That ski area remains open, but Boyne also owned the 436-vertical foot ski area alternately known as “Barn Mountain” and “Avalanche Peak” from 1972 to ’77. I can’t find a trailmap of this one, but here’s Boyne’s consolidation history: On Nub’s Nob and The Highlands When I say that Nub’s Nob and Boyne’s Highlands ski area are right across the street from each other, I mean they really are: Both are excellent ski areas - two of the best in the entire Midwest. On Granite Peak’s evolution under Midwest Family Ski Resorts I’ve written about this a lot, but check out Granite Peak AKA “Rib Mountain” before the company now known as Midwest Family Ski Resorts purchased it in 2000: And today: And it’s just like “what you’re allowed to do that?” On up-and-over chairlifts Bohemia may replace its double chair with a rare up-and-over machine, which would extend along the current line to the summit, and then continue to the bottom of Haunted Valley, effectively functioning as two chairlifts. Lonie explains the logic in the podcast, but if he succeeds here, this would be the first new up-and-over lift built in the United States since Stevens Pass’ Double Diamond-Southern Cross machine in 1987. I’m only aware of four other such machines in America, all of them in the Midwest: Little Switzerland recently revealed plans to replace the machine that makes up the 1 and 2 chairlifts with two separate quads next year. On Boho’s Nordic Spa I never thought hot tubs and parties and happiness were controversial. Then along came social media. And it turns out that when a ski area that primarily markets itself as a refuge for hardcore skiers also builds a base-area zone for these skiers to sink into another sort of indulgence at day’s end and then promotes these features, it make Angry Ski Bro VERY ANGRY. For most of human existence we had incentives to prevent ostentatious attention-seeking whining about peripheral things that had no actual impact on your life, and that incentive was Not Wanting To Get Your Ass Kicked. But some people interpreted the distance and anonymity of the internet as a permission slip to become the worst versions of themselves. And so we have a dedicated corps of morons trolling Boho’s socials with chest-thumping proclamations of #RealSkierness that rage against the $18 Nordic Spa fee taped onto each Boho $99 or $112 season pass. But when you go to Boho, what you see is this: And these people do not look angry. Because they are doing something fun and cool. Which is one more reason that I stopped reading social media comments several years ago and decided to base reality on living in it rather than observing it through my Pet Rectangle. On the Mad River Glen Co-Op and Betsy Pratt So far, the only successful U.S. ski area co-op is Mad River Glen , Vermont. Longtime owner Betsy Pratt orchestrated the transformation in 1995. She passed away in 2023 at age 95, giving her lots of years to watch the model endure. Black Mountain, New Hampshire, is in the midst of a similar transformation. On Mount Bohemia TV Boho is a strange, strange universe. Nothing better distills the mountain’s essence than Mount Bohemia TV – I mean that in the literal sense, in that each episode immerses you in this peculiar world, but also in an accidental quirk of its execution. Because the video staff keeps, in Lonie’s words, “losing the password,” Mount Bohemia has at least four official YouTube channels, each of which hosts different episodes of Mount Bohemia TV . Here’s episodes 1, 2, and 3 : 4 through 15 : 16 through 20 : And 21 and 22 : If anyone knows how to sort this out, I’m sure they’d appreciate the assist. Get full access to The Storm Skiing Journal and Podcast at www.stormskiing.com/subscribe

Nov 20

Podcast #218: Hatley Pointe, North Carolina Owner Deb Hatley

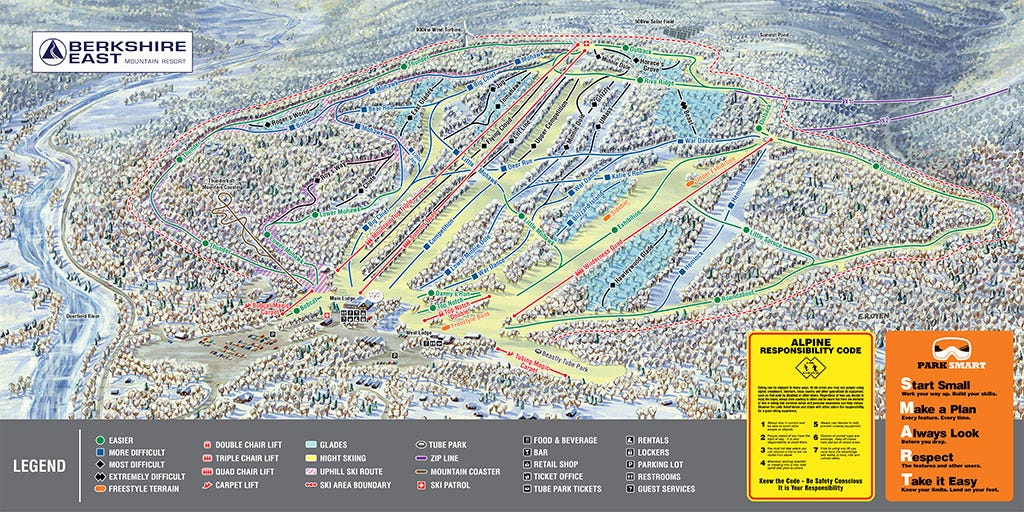

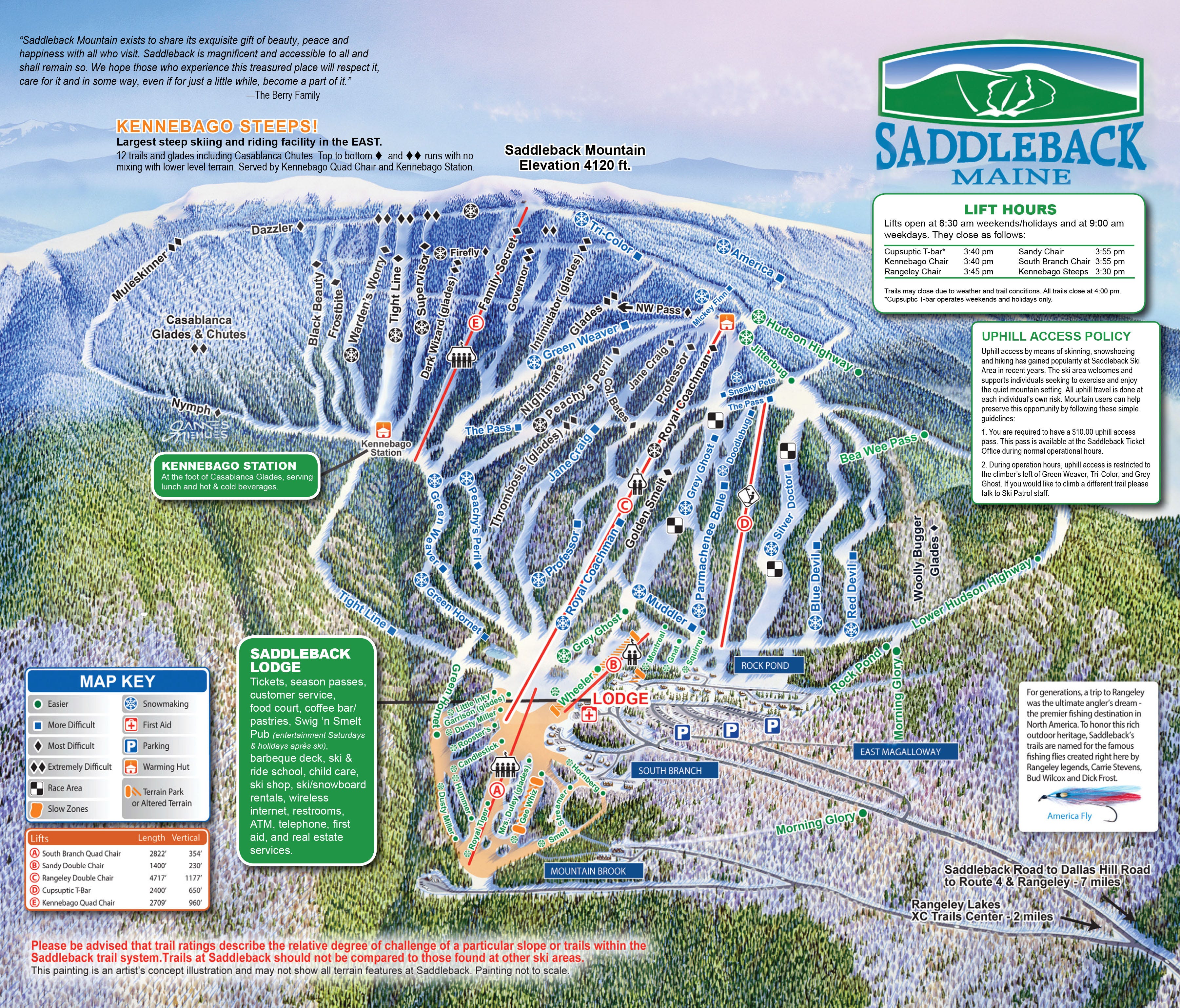

Who Deb Hatley, Owner of Hatley Pointe , North Carolina Recorded on July 30, 2025 About Hatley Pointe Click here for a mountain stats overview Owned by: Deb and David Hatley since 2023 - purchased from Orville English, who had owned and operated the resort since 1992 Located in: Mars Hill, North Carolina Year founded: 1969 (as Wolf Laurel or Wolf Ridge; both names used over the decades) Pass affiliations: Indy Pass, Indy+ Pass – 2 days, no blackouts Closest neighboring ski areas: Cataloochee (1:25), Sugar Mountain (1:26) Base elevation: 4,000 feet Summit elevation: 4,700 feet Vertical drop: 700 feet Skiable acres: 54 Average annual snowfall: 65 inches Trail count: 21 (4 beginner, 11 intermediate, 6 advanced) Lift count: 4 active (1 fixed-grip quad, 1 ropetow, 2 carpets); 2 inactive, both on the upper mountain (1 fixed-grip quad, 1 double) Why I interviewed her Our world has not one map, but many. Nature drew its own with waterways and mountain ranges and ecosystems and tectonic plates. We drew our maps on top of these, to track our roads and borders and political districts and pipelines and railroad tracks. Our maps are functional, simplistic. They insist on fictions. Like the 1,260-mile-long imaginary straight line that supposedly splices the United States from Canada between Washington State and Minnesota. This frontier is real so long as we say so, but if humanity disappeared tomorrow, so would that line. Nature’s maps are more resilient. This is where water flows because this is where water flows. If we all go away, the water keeps flowing. This flow, in turn, impacts the shape and function of the entire world. One of nature’s most interesting maps is its mountain map. For most of human existence, mountains mattered much more to us than they do now. Meaning: we had to respect these giant rocks because they stood convincingly in our way. It took European settlers centuries to navigate en masse over the Appalachians, which is not even a severe mountain range, by global mountain-range standards. But paved roads and tunnels and gas stations every five miles have muted these mountains’ drama. You can now drive from the Atlantic Ocean to the Midwest in half a day. So spoiled by infrastructure, we easily forget how dramatically mountains command huge parts of our world. In America, we know this about our country: the North is cold and the South is warm. And we define these regions using battle maps from a 19th Century war that neatly bisected the nation. Another imaginary line. We travel south for beaches and north to ski and it is like this everywhere, a gentle progression, a continent-length slide that warms as you descend from Alaska to Panama. But mountains disrupt this logic. Because where the land goes up, the air grows cooler. And there are mountains all over. And so we have skiing not just in expected places such as Vermont and Maine and Michigan and Washington, but in completely irrational ones like Arizona and New Mexico and Southern California. And North Carolina. North Carolina. That’s the one that surprised me. When I started skiing, I mean. Riding hokey-poke chairlifts up 1990s Midwest hills that wouldn’t qualify as rideable surf breaks, I peered out at the world to figure out where else people skied and what that skiing was like. And I was astonished by how many places had organized skiing with cut trails and chairlifts and lift tickets, and by how many of them were way down the Michigan-to-Florida slide-line in places where I thought that winter never came: West Virginia and Virginia and Maryland. And North Carolina. Yes there are ski areas in more improbable states. But Cloudmont, situated in, of all places, Alabama, spins its ropetow for a few days every other year or so. North Carolina, home to six ski areas spinning a combined 35 chairlifts, allows for no such ambiguity: this is a ski state. And these half-dozen ski centers are not marginal operations: Sugar Mountain and Cataloochee opened for the season last week, and they sometimes open in October. Sugar spins a six-pack and two detach quads on a 1,200-foot vertical drop. This geographic quirk is a product of our wonderful Appalachian Mountain chain, which reaches its highest points not in New England but in North Carolina, where Mount Mitchell peaks at 6,684 feet, 396 feet higher than the summit of New Hampshire’s Mount Washington. This is not an anomaly: North Carolina is home to six summits taller than Mount Washington, and 12 of the 20-highest in the Appalachians, a range that stretches from Alabama to Newfoundland. And it’s not just the summits that are taller in North Carolina. The highest ski area base elevation in New England is Saddleback, which measures 2,147 feet at the bottom of the South Branch quad (the mountain more typically uses the 2,460-foot measurement at the bottom of the Rangeley quad). Either way, it’s more than 1,000 feet below the lowest base-area elevation in North Carolina: Unfortunately, mountains and elevation don’t automatically equal snow. And the Southern Appalachians are not exactly the Kootenays. It snows some, sometimes, but not so much, so often, that skiing can get by on nature’s contributions alone - at least not in any commercially reliable form. It’s no coincidence that North Carolina didn’t develop any organized ski centers until the 1960s, when snowmaking machines became efficient and common enough for mass deployment. But it’s plenty cold up at 4,000 feet, and there’s no shortage of water. Snowguns proved to be skiing’s last essential ingredient. Well, there was one final ingredient to the recipe of southern skiing: roads. Back to man’s maps. Specifically, America’s interstate system, which steamrolled the countryside throughout the 1960s and passes just a few miles to Hatley Pointe’s west. Without these superhighways, western North Carolina would still be a high-peaked wilderness unknown and inaccessible to most of us. It’s kind of amazing when you consider all the maps together: a severe mountain region drawn into the borders of a stable and prosperous nation that builds physical infrastructure easing the movement of people with disposable income to otherwise inaccessible places that have been modified for novel uses by tapping a large and innovative industrial plant that has reduced the miraculous – flight, electricity, the internet - to the commonplace. And it’s within the context of all these maps that a couple who knows nothing about skiing can purchase an established but declining ski resort and remake it as an upscale modern family ski center in the space of 18 months. What we talked about Hurricane Helene fallout; “it took every second until we opened up to make it there,” even with a year idle; the “really tough” decision not to open for the 2023-24 ski season; “we did not realize what we were getting ourselves into”; buying a ski area when you’ve never worked at a ski area and have only skied a few times; who almost bought Wolf Ridge and why Orville picked the Hatleys instead; the importance of service; fixing up a broken-down ski resort that “felt very old”; updating without losing the approachable family essence; why it was “absolutely necessary” to change the ski area’s name; “when you pulled in, the first thing that you were introduced to … were broken-down machines and school buses”; Bible verses and bare trails and busted-up everything; “we could have spent two years just doing cleanup of junk and old things everywhere”; Hatley Pointe then and now; why Hatley removed the double chair; a detachable six-pack at Hatley?; chairlifts as marketing and branding tools; why the Breakaway terrain closed and when it could return and in what form; what a rebuilt summit lodge could look like; Hatley Pointe’s new trails; potential expansion; a day-ski area, a resort, or both?; lift-served mountain bike park incoming; night-skiing expansion; “I was shocked” at the level of après that Hatley drew, and expanding that for the years ahead; North Carolina skiing is all about the altitude; re-opening The Bowl trail; going to online-only sales; and lessons learned from 2024-25 that will build a better Hatley for 2025-26. What I got wrong When we recorded this conversation, the ski area hadn’t yet finalized the name of the new green trail coming off of Eagle – it is Pat’s Way (see trailmap above). I asked if Hatley intended to install night-skiing, not realizing that they had run night-ski operations all last winter. Why now was a good time for this interview Pardon my optimism, but I’m feeling good about American lift-served skiing right now. Each of the past five winters has been among the top 10 best seasons for skier visits, U.S. ski areas have already built nearly as many lifts in the 2020s (246) as they did through all of the 2010s (288), and multimountain passes have streamlined the flow of the most frequent and passionate skiers between mountains, providing far more flexibility at far less cost than would have been imaginable even a decade ago. All great. But here’s the best stat: after declining throughout the 1980s and ‘90s, the number of active U.S. ski areas stabilized around the turn of the century, and has actually increased for five consecutive winters : Those are National Ski Areas Association numbers, which differ slightly from mine. I count 492 active ski hills for 2023-24 and 500 for last winter , and I project 510 potentially active ski areas for the 2025-26 campaign. But no matter: the number of active ski operations appears to be increasing. But the raw numbers matter less than the manner in which this uptick is happening. In short: a new generation of owners is resuscitating lost or dying ski areas. Many have little to no ski industry experience. Driven by nostalgia, a sense of community duty, plain business opportunity, or some combination of those things, they are orchestrating massive ski area modernization projects, funded via their own wealth – typically earned via other enterprises – or by rallying a donor base. Examples abound. When I launched The Storm in 2019, Saddleback , Maine; Norway Mountain , Michigan; Woodward Park City; Thrill Hills, North Dakota; Deer Mountain , South Dakota; Paul Bunyan , Wisconsin; Quarry Road, Maine; Steeplechase , Minnesota; and Snowland, Utah were all lost ski areas. All are now open again, and only one – Woodward – was the project of an established ski area operator (Powdr). Cuchara, Colorado and Nutt Hill, Wisconsin are on the verge of re-opening following decades-long lift closures. Bousquet , Massachusetts; Holiday Mountain , New York; Kissing Bridge , New York; and Black Mountain , New Hampshire were disintegrating in slow-motion before energetic new owners showed up with wrecking balls and Home Depot frequent-shopper accounts. New owners also re-energized the temporarily dormant Sandia Peak , New Mexico and Tenney , New Hampshire. One of my favorite revitalization stories has been in North Carolina, where tired, fire-ravaged, investment-starved, homey-but-rickety Wolf Ridge was falling down and falling apart. The ski area’s season ended in February four times between 2018 and 2023. Snowmaking lagged. After an inferno ate the summit lodge in 2014, no one bothered rebuilding it. Marooned between the rapidly modernizing North Carolina ski trio of Sugar Mountain, Cataloochee, and Beech, Wolf Ridge appeared to be rapidly fading into irrelevance. Then the Hatleys came along. Covid-curious first-time skiers who knew little about skiing or ski culture, they saw opportunity where the rest of us saw a reason to keep driving. Fixing up a ski area turned out to be harder than they’d anticipated, and they whiffed on opening for the 2023-24 winter. Such misses sometimes signal that the new owners are pulling their ripcords as they launch out of the back of the plane, but the Hatleys kept working. They gut-renovated the lodge, modernized the snowmaking plant, tore down an SLI double chair that had witnessed the signing of the Declaration of Independence. And last winter, they re-opened the best version of the ski area now known as Hatley Pointe that locals had seen in decades. A great winter – one of the best in recent North Carolina history – helped. But what I admire about the Hatleys – and this new generation of owners in general – is their optimism in a cultural moment that has deemed optimism corny and naïve. Everything is supposed to be terrible all the time, don’t you know that? They didn’t know, and that orientation toward the good, tempered by humility and patience, reversed the long decline of a ski area that had in many ways ceased to resonate with the world it existed in. The Hatleys have lots left to do: restore the Breakaway terrain, build a new summit lodge, knot a super-lift to the frontside. And their Appalachian salvage job, while impressive, is not a very repeatable blueprint – you need considerable wealth to take a season off while deploying massive amounts of capital to rebuild the ski area. The Hatley model is one among many for a generation charged with modernizing increasingly antiquated ski areas before they fall over dead. Sometimes, as in the examples itemized above, they succeed. But sometimes they don’t. Comebacks at Cockaigne and Hickory, both in New York, fizzled. Sleeping Giant, Wyoming and Ski Blandford, Massachusetts both shuttered after valiant rescue attempts. All four of these remain salvageable, but last week, Four Seasons, New York closed permanently after 63 years. That will happen. We won’t be able to save every distressed ski area, and the potential supply of new or revivable ski centers, barring massive cultural and regulatory shifts, will remain limited. But the protectionist tendencies limiting new ski area development are, in a trick of human psychology, the same ones that will drive the revitalization of others – the only thing Americans resist more than building something new is taking away something old. Which in our country means anything that was already here when we showed up. A closed or closing ski area riles the collective angst, throws a snowy bat signal toward the night sky, a beacon and a dare, a cry and a plea: who wants to be a hero? Podcast Notes On Hurricane Helene Helene smashed inland North Carolina last fall, just as Hatley was attempting to re-open after its idle year. Here’s what made the storm so bad: On Hatley’s socials Follow: On what I look for at a ski resort On the Ski Big Bear podcast In the spirit of the article above, one of the top 10 Storm Skiing Podcast guest quotes ever came from Ski Big Bear, Pennsylvania General Manager Lori Phillips: “You treat everyone like they paid a million dollars to be there doing what they’re doing” On ski area name changes I wrote a piece on Hatley’s name change back in 2023: Ski area name changes are more common than I’d thought. I’ve been slowly documenting past name changes as I encounter them, so this is just a partial list, but here are 93 active U.S. ski areas that once went under a different name. If you know of others, please email me . On Hatley at the point of purchase and now Gigantic collections of garbage have always fascinated me. That’s essentially what Wolf Ridge was at the point of sale: It’s a different place now: On the distribution of six-packs across the nation Six-pack chairlifts are rare and expensive enough that they’re still special, but common enough that we’re no longer amazed by them. Mostly - it depends on where we find such a machine. Just 112 of America’s 3,202 ski lifts (3.5 percent) are six-packs, and most of these (75) are in the West (60 – more than half the nation’s total, are in Colorado, Utah, or California). The Midwest is home to a half-dozen six-packs, all at Boyne or Midwest Family Ski Resorts operations, and the East has 31 sixers, 17 of which are in New England, and 12 of which are in Vermont. If Hatley installed a sixer, it would be just the second such chairlift in North Carolina, and the fifth in the Southeast, joining the two at Wintergreen, Virginia and the one at Timberline, West Virginia. On the Breakaway fire Wolf Ridge’s upper-mountain lodge burned down in March 2014. Yowza: On proposed expansions Wolf Ridge’s circa 2007 trailmap teases a potential expansion below the now-closed Breakaway terrain: Taking our time machine back to the late ‘80s, Wolf Ridge had envisioned an even more ambitious expansion: The Storm explores the world of lift-served skiing year-round. Join us. Get full access to The Storm Skiing Journal and Podcast at www.stormskiing.com/subscribe

Nov 10

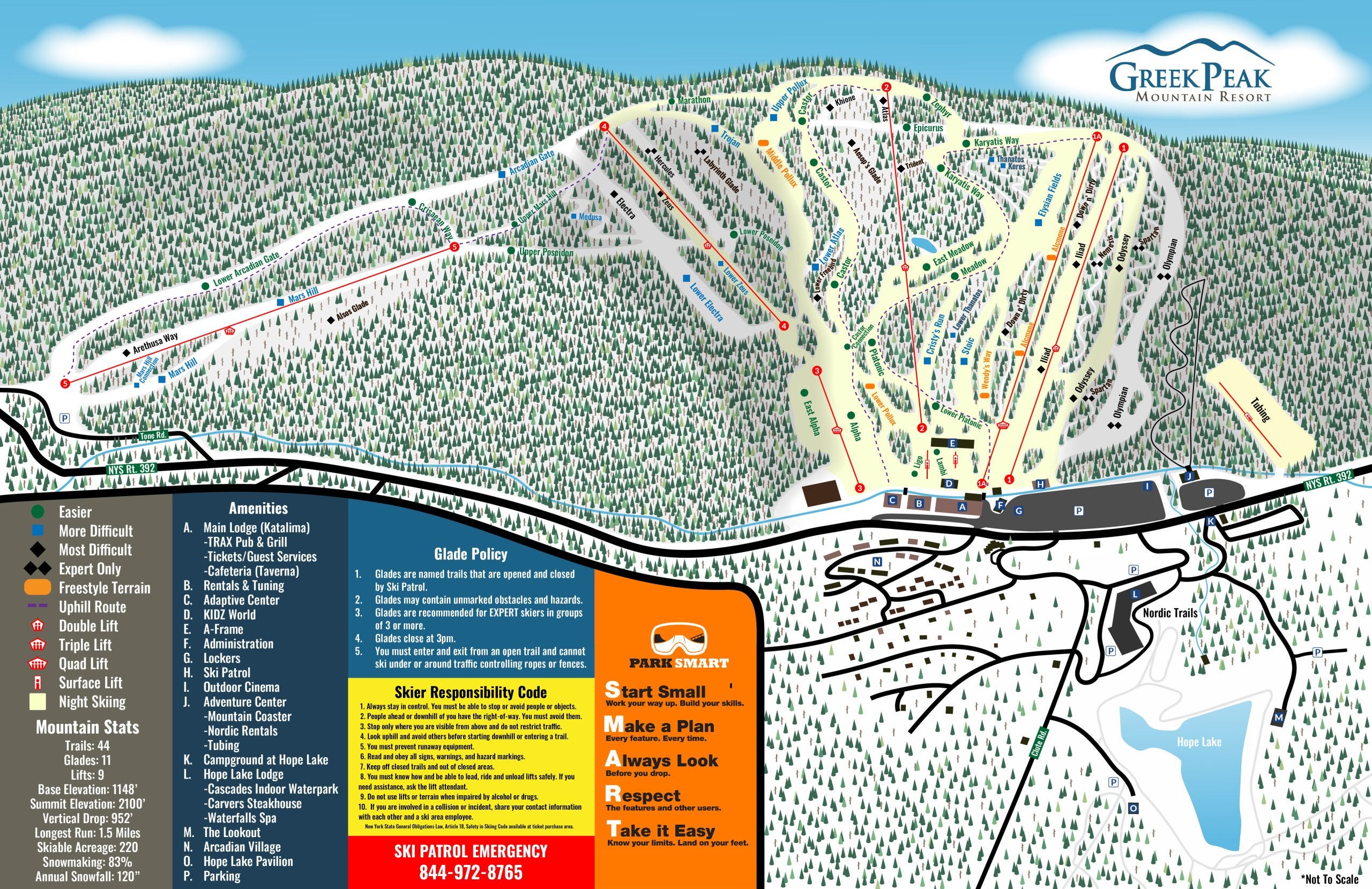

Podcast #217: Greek Peak NY President Wes Kryger & Mountain Ops VP Ayden Wilber

Who Wes Kryger, President and Ayden Wilber, Vice President of Mountain Operations at Greek Peak , New York Recorded on June 30, 2025 About Greek Peak Click here for a mountain stats overview Owned by: John Meier Located in: Cortland, New York Year founded: 1957 – opened Jan. 11, 1958 Pass affiliations: Indy Pass, Indy+ Pass – 2 days Closest neighboring U.S. ski areas: Labrador (:30), Song (:31) Base elevation: 1,148 feet Summit elevation: 2,100 feet Vertical drop: 952 feet Skiable acres: 300 Average annual snowfall: 120 inches Trail count: 46 (10 easier, 16 more difficult, 15 most difficult, 5 expert, 4 terrain parks) Lift count: 8 (1 fixed-grip quad, 2 triples, 3 doubles – view Lift Blog’s inventory of Greek Peak’s lift fleet) Why I interviewed them No reason not to just reprint what I wrote about the bump earlier this year : All anyone wants from a family ski trip is this: not too far, not too crowded, not too expensive, not too steep, not too small, not too Bro-y. Terrain variety and ample grooming and lots of snow, preferably from the sky. Onsite lodging and onsite food that doesn’t taste like it emerged from the ration box of a war that ended 75 years ago. A humane access road and lots of parking. Ordered liftlines and easy ticket pickup and a big lodge to meet up and hang out in. We’re not too picky you see but all that would be ideal. My standard answer to anyone from NYC making such an inquiry has been “hahaha yeah get on a plane and go out West.” But only if you purchased lift tickets 10 to 16 months in advance of your vacation. Otherwise you could settle a family of four on Mars for less than the cost of a six-day trip to Colorado. But after MLK Weekend, I have a new answer for picky non-picky New Yorkers: just go to Greek Peak. Though I’d skied here in the past and am well-versed on all ski centers within a six-hour drive of Manhattan, it had not been obvious to me that Greek Peak was so ideally situated for a FamSki. Perhaps because I’d been in Solo Dad tree-skiing mode on previous visits and perhaps because the old trailmap presented the ski area in a vertical fortress motif aligned with its mythological trail-naming scheme: But here is how we experienced the place on one of the busiest weekends of the year: 1. No lines to pick up tickets. Just these folks standing around in jackets, producing an RFID card from some clandestine pouch and syncing it to the QR code on my phone. 2. Nothing resembling a serious liftline outside of the somewhat chaotic Visions “express” (a carpet-loaded fixed-grip quad). Double and triple chairs, scattered at odd spots and shooting off in all directions, effectively dispersing skiers across a broad multi-faced ridge. The highlight being this double chair originally commissioned by Socrates in 407 B.C.: 3. Best of all: endless, wide-open, uncrowded top-to-bottom true greens – the only sort of run that my entire family can ski both stress-free and together. Those runs ambled for a thousand vertical feet. The Hope Lake Lodge, complete with waterpark and good restaurant, sits directly across the street. A shuttle runs back and forth all day long. Greek Peak, while deeper inland than many Great Lakes-adjacent ski areas, pulls steady lake-effect, meaning glades everywhere (albeit thinly covered). It snowed almost the entire weekend, sometimes heavily. Greek Peak’s updated trailmap better reflects its orientation as a snowy family funhouse (though it somewhat obscures the mountain’s ever-improving status as a destination for Glade Bro): For MLK 2024, we had visited Camelback, seeking the same slopeside-hotel-with-waterpark-decent-food-family-skiing combo. But it kinda sucked. The rooms, tinted with an Ikea-by-the-Susquehanna energy, were half the size of those at Greek Peak and had cost three times more. Our first room could have doubled as the smoking pen at a public airport (we requested, and received, another). The hill was half-open and overrun with people who seemed to look up and be genuinely surprised to find themselves strapped to snoskis. Mandatory parking fees even with a $600-a-night room; mandatory $7-per-night, per-skier ski check (which I dodged); and perhaps the worst liftline management I’ve ever witnessed had, among many other factors, added up to “let’s look for something better next year.” That something was Greek Peak, though the alternative only occurred to me when I attended an industry event at the resort in September and re-considered its physical plant undistracted by ski-day chaos. Really, this will never be a true alternative for most NYC skiers – at four hours from Manhattan, Greek Peak is the same distance as far larger Stratton or Mount Snow. I like both of those mountains, but I know which one I’m driving my family to when our only time to ski together is the same time that everyone else has to ski together. What we talked about 116,000 skier visits; two GP trails getting snowmaking for the first time; top-to-bottom greens; Greek Peak’s family founding in the 1950s – “any time you told my dad [Al Kryger] he couldn’t do it, he would do it just to prove you wrong”; reminiscing on vintage Greek Peak; why Greek Peak made it when similar ski areas like Scotch Valley went bust; the importance of having “hardcore skiers” run a ski area; does the interstate matter?; the unique dynamics of working in – and continuing – a family business; the saga and long-term impact of building a full resort hotel across the street from the ski area; “a ski area is liking running a small municipality”; why the family sold the ski area more than half a century after its founding; staying on at the family business when it’s no longer a family business; John Meier arrives; why Greek Peak sold Toggenburg; long-term snowmaking ambitions; potential terrain expansion – where and how much; “having more than one good ski season in a row would be helpful” in planning a future expansion; how Greek Peak modernized its snowmaking system and cut its snowmaking hours in half while making more snow; five times more snowguns; Great Lakes lake-effect snow; Greek Peak’s growing glade network and long evolution from a no-jumps-allowed old-school operation to today’s more freewheeling environment; potential lift upgrades; why Greek Peak is unlikely to ever have a high-speed lift; keeping a circa 1960s lift made by an obscure company running; why Greek Peak replaced an old double with a used triple on Chair 3 a few years ago; deciding to renovate or replace a lift; how the Visions 1A quad changed Greek Peak and where a similar lift could make sense; why Greek Peak shortened Chair 2; and the power of Indy Pass for small, independent ski areas. What I got wrong On Scotch Valley ski area I said that Scotch Valley went out of business “in the late ‘90s.” As far as I can tell, the ski area’s last year of operation was 1998. At its peak, the 750-vertical-foot ski area ran a triple chair and two doubles serving a typical quirky-fun New York trail network. I’m sorry I missed skiing this one. Interestingly, the triple chair still appears to operate as part of a summer camp . I wish they would also run a winter camp called “we’re re-opening this ski area”: On Toggenburg I paraphrased a quote from Greek Peak owner John Meier, from a story I wrote around the 2021 closing of Toggenburg. Here’s the quote in full: “Skiing doesn’t have to happen in New York State,” Meier said. “It takes an entrepreneur, it takes a business investor. You gotta want to do it, and you’re not going to make a lot of money doing it. You’re going to wonder why are you doing this? It’s a very difficult business in general. It’s very capital-intensive business. There’s a lot easier ways to make a buck. This is a labor of love for me.” And here’s the full story, which lays out the full Togg saga: Podcast Notes On Hope Lake Lodge and New York’s lack of slopeside lodging I’ve complained about this endlessly, but it’s strange and counter-environmental that New York’s two largest ski areas offer no slopeside lodging. This is the same oddball logic at work in the Pacific Northwest, which stridently and reflexively opposes ski area-adjacent development in the name of preservation without acknowledging the ripple effects of moving 5,000 day skiers up to the mountain each winter morning. Unfortunately Gore and Whiteface are on Forever Wild land that would require an amendment to the state constitution to develop, and that process is beholden to idealistic downstate voters who like the notion of preservation enough to vote abstractly against development, but not enough to favor Whiteface over Sugarbush when it’s time to book a family ski trip and they need convenient lodging. Which leaves us with smaller mountains that can more readily develop slopeside buildings: Holiday Valley and Hunter are perhaps the most built-up, but West Mountain has a monster development grinding through local permitting processes: Greek Peak built the brilliant Hope Lake Lodge, a sprawling hotel/waterpark with wood-trimmed, fireplace-appointed rooms directly across the street from the ski area. A shuttle connects the two. On the “really, really bad” 2015 season Wilber referred to the “really, really bad” 2015 season. Here’s the Kottke end-of-season stats comparing 2015-16 snowfall to the previous three winters, where you can see the Northeast just collapse into an abyss: Month-by-month (also from Kottke): Fast forward to Kottke’s 2022-23 report, and you can see just how terrible 2015-16 was in terms of skier visits compared to the seasons immediately before and after: On Greek Peak’s old masterplan with a chair 6 I couldn’t turn up the masterplan that Kryger referred to with a Chair 6 on it, but the trailmap did tease a potential expansion from around 2006 to 2012, labelled as “Greek Peak East”: On Great Lakes lake-effect snow This is maybe the best representation I’ve found of the Great Lakes’ lake-effect snowbands: On Greek Peak’s Lift 2 What a joy this thing is to ride: An absolute time machine: The lift, built in 1963, looks rattletrap and bootleg, but it hums right along. It is the second-oldest operating chairlift in New York State, after Snow Ridge’s 1960 North Hall double chair, and the fourth-oldest in the Northeast (Mad River Glen’s single, dating to 1948, is King Gramps of the East Coast). It’s one of the 20-oldest operating chairlifts in America: As Wilber says, this lift once ran all the way to the base. They shortened the lift sometime between 1995 and ’97 to scrape out a larger base-area novice zone. Greek Peak’s circa 1995 trailmap shows the lift extending to its original load position: Following Pico’s demolition of the Bonanza double this offseason, Greek Peak’s Chair 2 is one of just three remaining Carlevaro-Savio lifts spinning in the United States: The Storm explores the world of lift-served skiing year-round. Join us. Get full access to The Storm Skiing Journal and Podcast at www.stormskiing.com/subscribe

Nov 2

Podcast #216: Treetops General Manager Barry Owens